Shooting with History: The Leidolf Lordomat

I bought a little piece of history last month.

I’d been idly wondering if a rangefinder camera might suit my shooting style. Rangefinders are small, subtle cameras — they don’t need the space inside to handle the big flipping mirror arrangement of an SLR, and losing the mirror means the lens can be smaller, too. Rangefinders are so associated with street photography that they effectively defined the genre, in the hands of Henri Cartier-Bresson. Pocketable and quiet, they’re an elegant weapon, for a more civilised age.

Rangefinders had most of their market share eaten by film and digital SLRs even before the advent of high quality mirrorless compacts. But they still have their proponents, and Leica — whose name springs to mind when any photographer thinks “rangefinder” — are still going strong. Unfortunately, the Leica rangefinder’s history, reputation for quality, and market positioning puts their digital range a long way out of my wallet’s reach. Hey, just the black-and-white one costs £5,000. (No, I’m not kidding. Leica’s M Monochrom rangefinder is a digital camera that only shoots in black and white. And for £5,000, they don’t even throw in a lens.)

Even an old-school, secondhand film Leica will set you back many hundreds of pounds. But there are alternatives, as I discovered walking past Bernard Hunter’s shop a few weeks ago. This camera cave on North Street in Bedminster — which feels like an obsessive equipment hoarder decided to set up a cash register in his living room — had a “1950s Rangefinder/Full Working Order” on display in its window.

It was this Leidolf Lordomat.

Leidolf were an optics company who originally made microscope lenses, and branched out into cameras from 1948 until the company closed in 1962. They were based in Wetzlar, where Leica first developed their 35mm cameras.

When I first saw the Lordomat, I’d never heard of them. But for £60, in full working order, I thought it was probably worth taking a punt, and I’m glad that I did.

The Lordomat is a thing of beauty. That it was manufactured in postwar Germany before they started putting up the Berlin Wall, and still works perfectly today, is a testament to its build quality. The film wind-on sounds lovely, but even that loveliness is eclipsed by the graceful “schluunck” of the shutter.

The lens is no Leica, but a 50mm f/2.8 is a fine walkaround lens for a street camera. It’s got a pleasant curved-blade circular aperture, and the quality seems pretty good. It’s hard to convey perfectly here, because I don’t have a decent negative scanner, so all these shots are scans from 4x6 glossy prints. These are from the first test roll of Ilford HP5 Plus I threw through the camera in a couple of days, just to make sure it worked.

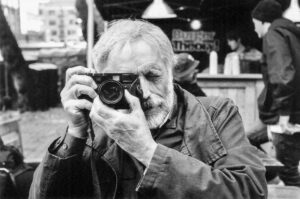

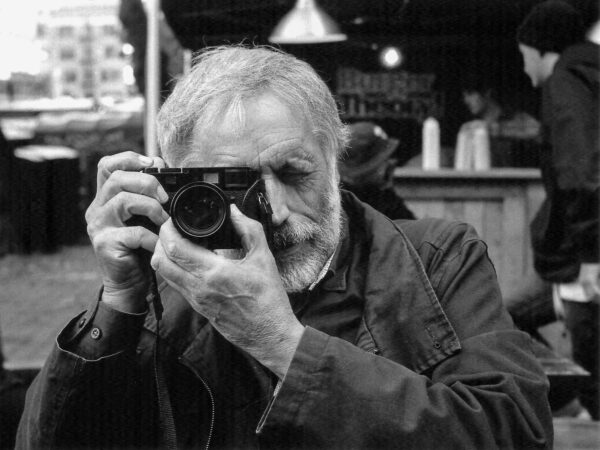

My favourite is this photo of my friend Paul, shooting back at me with his Leica M9:

I surprised myself by getting the exposure about right for most of the pictures. The Lordomat has no electronics whatsoever, so you’re either metering by eye, carrying a light meter (I have a Gossen Sixtry) or using a phone app. Mostly I was judging by eye, with occasional help from the Gossen.

It’s most definitely a more subtle camera than my normal camera, the Canon 6D. Even with Canon’s smallest lens, the 40mm “pancake”, the 6D is still a lot bigger.

Compared to the 6D, though, an elderly rangefinder can be pretty hard to use. As I said, there’s no autoexposure: You think about the light more, which is good practice, but I wouldn’t want to have to meter manually all the time.

The focus is manual, too, though helped along by the rangefinder.

If you’ve never used a rangefinder, here’s how the Lordomat works: Unlike a DSLR, you’re not looking through the camera’s main lens. Instead, you’re looking through the viewfinder “window” in the top corner (top right, viewed from the front.) In the other top corner — as far away horizontally as possible — there’s another window, the rangefinder lens. Through the viewfinder, you see the overall view, and superimposed on a rectangular area in the middle, a view from the rangefinder lens.

In a “coupled” rangefinder like the Lordomat, moving the lens’s focus ring also rotates a mirror or prism that changes the angle of the rangefinder part of the image.

It works just like the depth perception of a pair of human eyes. If your subject, in the central area of the picture, isn’t in focus, the small superimposed image will be offset from the main view, to the left or to the right, so you’ll be “seeing double”. You adjust the focus until the superimposed image lines up with the normal image. When an object is no longer “doubled” in the centre section of the viewfinder, you know the lens is now focusing on it perfectly1.

Designed for accurate manual focus, the Lordon lens’s focus ring turns a full 360 degrees from close focus to infinity, much further than the manual focus ring on a typical modern autofocus lens. So, focusing can take a while.

On the plus side, the Lordomat does have a depth of field scale so you can use zone focusing, basically setting up your focus region in advance, and reading off your minimum and maximum focus distance — in feet! — without even looking through the viewfinder.

The Lordomat has plenty of quirks. As with all rangefinders, it’s easy to take a photo with the lens cap on, as you can still see just fine through the viewfinder window. Plus there’s parallax error, as the viewfinder is offset from the lens, so your framing might be a bit off close-up. And the shutter release is hair-trigger sensitive — it’s the lever on the side of the lens, not the button-looking thing on the top, incidentally — so I’ve taken a fair few photos of the floor as I’ve been walking around.

Me with the Lordomat. Photo by Paul Chapman; shot, appropriately enough, with a Leica M9 rangefinder.

But because it’s small, and the viewfinder is in the top-left corner, much of your face — an eye, your smile — is unobscured when taking a photo. There’s less separation between the photographer and the scene, both physically and emotionally, I think, than with an SLR. It’s also generally less intimidating having a rangefinder — with smaller lenses as well as smaller bodies — pointed at you. As long as you’ve wound on in advance, there’s no mirror to flap about when you shoot, either, so taking a photo is significantly less noisy.

I can see why some of the biggest names in street photography shot — and still shoot — with rangefinders.

This market will be facing further disruption over the next few years, as little mirrorless digitals continue to innovate in the “small and unobtrusive but still very high quality” sphere. But until I can afford to spend nearly a thousand pounds putting a toe in that kind of water, I’m think I’m probably just going to be buying the occasional roll of film for the Lordomat. My friend Chris has already suggested that I give Kodak’s Ektar 100 a try in it, so I’m popping back to Bernard Hunter for some tomorrow.

Digital is always going to be my main medium, but an old film camera can be a really good way of trying something different. With the Leidolf, I’m shooting with a piece of the past, wondering what else it’s seen, how many photos were snapped by its previous owners through the last six decades. And the fully manual shooting — not to mention the fact that every shot costs money — makes me think a little more while I’m snapping.

If you want to know more about how rangefinders work, the best explanation I can find is photozone’s SLR versus Rangefinder. ↩

1 Comment

Retrofitting | Gothick.org.uk

November 7, 2014[…] wasn’t sure about running colour film though the Lordomat. It seemed a little anachronistic, given that colour film wasn’t generally available when the […]