When Books Have History

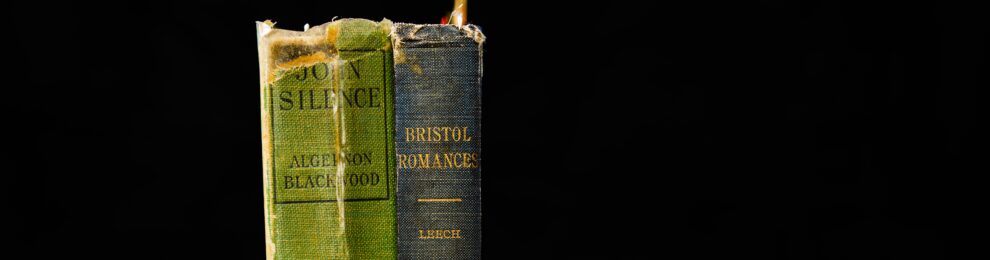

While I enjoy my Kindle for portability and versatility, my recent One Mile Matt project has had me diving into proper physical books for one reason or another. I’d almost forgotten how nice it can be to feel and smell the age of an old book. For October, Best-Smelling Book of the Month Award 1 goes to Bristol Libraries’ reserve store copy of John Silence, a collection of tales from Algernon Blackwood. It seems to have collected more than its fair share of the reserve store’s heady incense of ageing buckram and foxed paper.

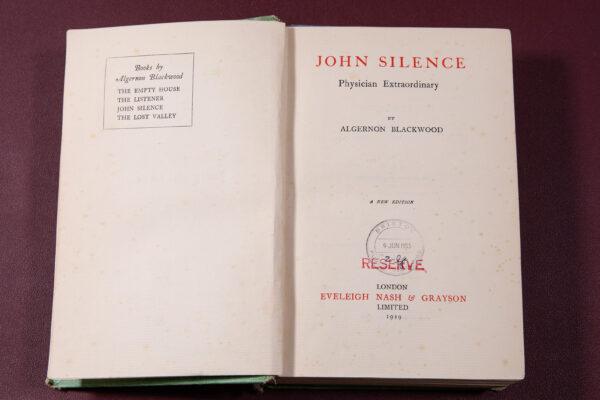

It’s the “new” 1929 edition, which I’m guessing may have been created because the first edition, published 1908, featured a swastika on the cover and the title page. I’m not sure exactly when the symbol stopped being seen as a cheery and slightly esoteric symbol of eastern religions and was hijacked by the Nazis into something that no right-thinking person would stick on a cover to sell more books, but 1929 doesn’t sound like it would be out of the ballpark…

Blackwood, incidentally, would almost certainly have come across the swastika during his studies with the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, whose reading materials included many symbols of various world religions. 2 My current interest (obsession? No, I’m going to say interest) in these eccentrics is what led me to his John Silence stories, a collection of tales featuring the eponymous psychic detective.

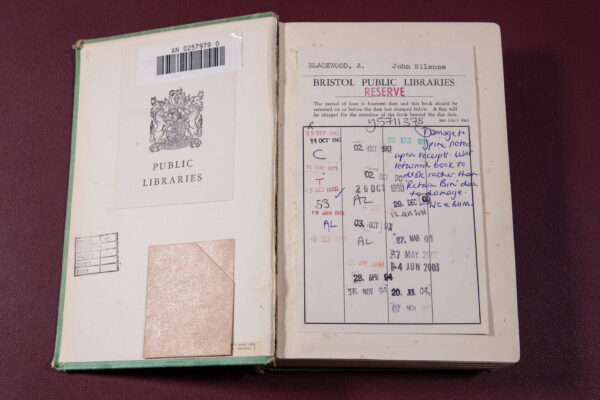

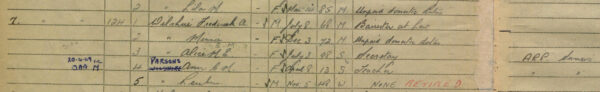

There are other interesting physical details of this particular copy of John Silence: as I idly looked through the various library additions inside the front cover, I lifted the date due slip to see if there was an older one underneath and found this:

And yes, I believe it’s that Spencer-Churchill family. My best guess is that the book was once owned by Augusta Warburton, daughter of George Drought Warburton, who married Lord Edward Spencer-Churchill, son of the 6th Duke of Marlborough, in 1874. I don’t seem to be able to find out much about her. She’s listed as “Chairman of the Women’s Section of the British Legion” under her 1935 New Years’ Honours CBE, and tantalisingly I can see her picture at the Imperial War Museum, under a section titled “FIRST WORLD WAR PORTRAITS (WOMEN’S WAR WORK) CLASSIFIED COLLECTION”, but can’t dig out much more than that from their site.

In the same week I made that little discovery, I was walking through Clifton Village on the way to grab a coffee from Twelve when I noticed that Rachel’s and Michael’s Antiques had tables full of secondhand books on display. “I won’t buy anything,” I told myself. “I’ve already got more than enough books,” I said. “Even one more on the ‘incoming’ shelf would be too many,” I said.

Yes, obviously I bought one. It would have been hard to resist a deckle-edged 1884 book called Bristol Romances even if I hadn’t, on a quick flip through, found stories about William Canynge’s strange relationship with an alchemist, a tale of the Hot Wells, and a reference to Sneyd Park’s Pitch and Pay Lane, apparently a relic of an earlier global pandemic, being the place where the town and countryside folk met each other to exchange food for money at a safe distance.

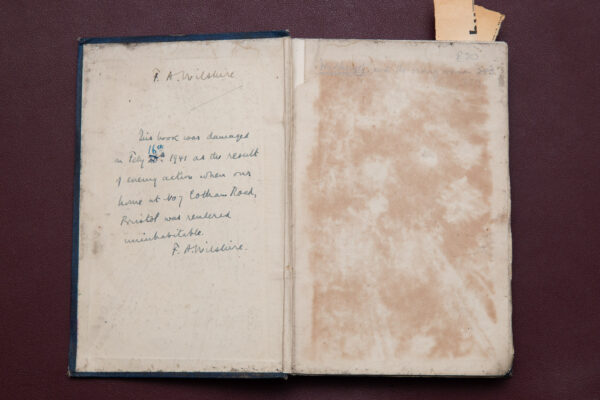

Then I flipped to the inside front cover, and found this:

This book was damaged on February 16th 1941 as the result of enemy action when our home at No. 7 Cotham Road, Bristol was rendered uninhabitable.

F A Wilshire

I mean, if that’s not worth forking out £20 for, I don’t know what is.

This blog’s genealogy and historical research correspondent 3, Margaret, found the 1939 census records for the family, so among other things I can tell you that Frederick A Wilshire was a Barrister at Law who would have been 72 when the house was bombed in 1941. In 1939 he was living with his wife, Minnie, and, among others, Alice — I presume their daughter — who’s noted as being on air-raid precaution duties. 4

(The author of Bristol Romances, Joseph Leech, is an interesting character: owner of the Bristol Times he was also its pseudonymous “Bristol Church-Goer”, secret reviewer of church services, “mystery shopper”-style, and made enough money from his newspaper business to have Burwalls built. Along the way he ran Bristol Waterworks and was deputy chairman of the Clifton Bridge company, and had time to write these stories, which are apparently rather fictionalised accounts, based only loosely on Bristol history.)

Pleasingly, these two books are linked by another bit of local history. John Silence has a label showing that it was bought at William George’s Sons Ltd., 89 Park Street; the publisher of Bristol Romances is William George and Son (presumably at least one extra son appeared between 1884 and 1929…)

A quick search turned up a blog post from Thinking of the Days: A day of remembering the bookshops in Bristol where I found a historical picture of one of William George’s Park Street bookshops, and I have, in fact, bought books in that very building!

William George’s Sons sold their business to Blackwells in 1929, but apparently the Park Street bookshop kept the name William George until just before I arrived in Bristol in the mid-1990s, and the Blackwells at 89 Park Street is definitely a bookshop I spent plenty of time and money in. I must have only narrowly missed shopping there when it was still William George’s. 5

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’m at an exciting bit in the John Silence story Secret Worship, so I’d best get back to my reading…

- An honour I just invented and which will almost certainly not become an ongoing monthly award.[↩]

- He joined in 1900, achieving Philosophus grade by 1904.[↩]

- And, entirely coincidentally of course, my stepmum.[↩]

- I think. I’m no expert at reading old census entries.[↩]

- sadly, the last time I was in the building, it had turned into a now-defunct branch of Jamie’s Italian, after Blackwell’s closed.[↩]